(photo: Nader Khouri Photography)

(photo: Nader Khouri Photography)

I don’t get star struck. There is something about the notion of being starstruck I find completely absurd. Girls going apoplectic over a 15 year old “hottie”? Waiting for five hours in the broiling sun to get a glimpse of an actor? Or stalking your favorite pop star for that matter? I just don’t get it.

But then again, I’ve been trying to shake the weirdest feeling. One of those feelings where I’ve been run over, had my first kiss, finished a marathon, and won a million dollars… all in the same day. Shit. Is this what being star struck is like? It has been a week since I had the pleasure of hosting René Redzepi here in San Francisco, and I’m still feeling all a quiver.

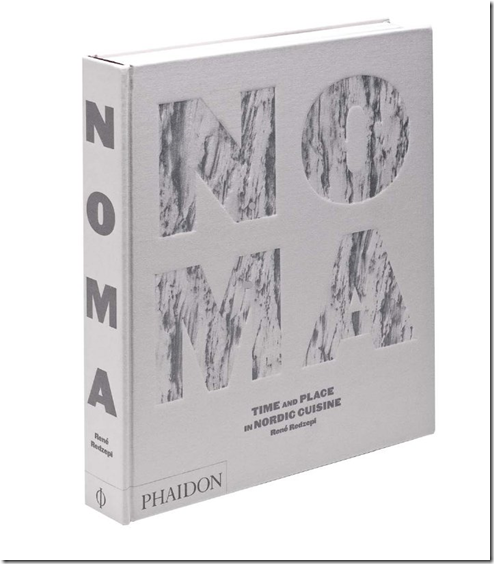

(Photo: Phaidon Press)

Let’s be clear here, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. With Celia on vacation in Istanbul, I’d been manning the fort at Omnivore for a few weeks. Sure, I had no problem running a few events. Rock Star chefs? I can handle it. No problem Celia!

And then one day it started – a delivery man came with an entire palette of boxes.

Inside? The Noma Cookbook. 1300 pounds of the Noma cookbook, to be exact. It’s an obscenely beautiful book, put out by Phaidon, weighs nearly five pounds, and is covered in gray cloth. Three quarters of the book are striking photos of the gastronomic creations that have catapulted René Redzepi’s Noma to stardom; this year, Noma has been named the best restaurant in the world.

(photo: Nader Khouri Photography)

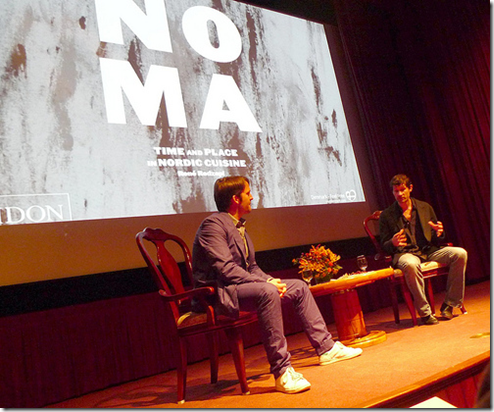

On Sunday night, I couldn’t sleep. Thinking about the Monday lineup was exhausting. A three o’clock signing at the bookstore, close up shop, take all the books and head over to Delancey Street Theater for a two hour talk with Redzepi and Daniel Patterson, check people in, sell books. Racing thoughts kept me awake, terrified. What if I can’t handle it? What if we screw up? What if someone has broken into the bookstore and stolen all 1300 pounds of books — a serious fear brought on by my sleepless delirium.

In hindsight, of course, I had nothing to worry about.

What can I tell you about René Redzepi?

In only a few hours I was able to unequivocally deduce that he is one of the most gracious, intelligent, driven people I have met. (He also has a voracious appetite for knowledge, and snagged some of my favorite historical books on food, including rare copies of Jane Grigson’s Vegetable Book and Fruit Book, and Marinetti’s The Futurist Cookbook.) He took the time to sign and personalize every book, take pictures with adoring fans, and joke around in between. And he’s adorable.

When he spoke, I took notes – 12 pages of notes – which I’m going to do my best to recount without sounding like a rambling idiot.

René Redzepi and Daniel Patterson Do Stand Up

What happens when you get two chefs on stage together and a captive audience of 150 people? Somehow, they both managed to utter the phrase Seal-Fuckers and everyone finds it hilarious.

For two hours, what unfolded on stage was something incredible. Something I believe everyone will be thinking about for years to come. A combination of a comedy routine, storytelling, and critical analysis. I think it’s safe to say the audience was thoroughly moved by the presentation.

In his introduction, Daniel Patterson – of Coi in San Francisco and the newly opened Plum in Oakland – was clearly excited to be sharing the stage with Redzepi. And who wouldn’t be, really?

Patterson described Redzepi as the master of “cooking from your own place”, and extolled what makes him the best in the kitchen: “Intuition – he’s a scary good cook. Super distinctive and sharp. Watching his mind work? So, so, fast.” To be a chef of this caliber, it is not just about skill, it’s also something deeper. “There’s an incredible warmth, a very strong emotional foundation. There is real joy.”

As the talk commenced, the audience was instructed to look through a little cloth bag under each seat filled with freshly foraged herbs, hay, and a small packet of Angelica root (known in Chinese medicine as Dong Quai). As you opened the bag, fragrance exploded and you were instantly transported to the forest. The bag was so fragrant, in fact, that after leaving it overnight in my leather purse, I’m beginning to believe it has permanently scented my handbag.

It Starts In Childhood

Some of Redzepi’s earliest influences were from an upbringing spent traveling between Denmark and his father’s native country, Macedonia.

In Macedonia, if you wanted food, you grew it. And what you didn’t grow, you traded with your neighbors, or perhaps picked up at the baker. Driven mostly by poverty, but also a sense of pride in their own food, life there was back to the land. The people were poor but not wanting in good food.

It’s not surprising to hear Redzepi didn’t drink soda until he was an adult. Special drinks were syrup over rose petals, or milk (provided that you milked the cow), but mostly, there was water.

In contrast, Denmark in the 1980’s was captivated with the microwave and ready meals. As a child, Redzepi recalled some embarrassment about heading to Macedonia (particularly while his Danish peers were off spending their summers in Italy or France). In hindsight, experiences foraging, farming, and eating from the land have only served him well. His family grew peppers and watermelon. Watermelon, he joked, is the perfect food:”You eat, you drink, and you wash your face”.

But good things don’t last forever, Redzepi lamented, “when the war came, people fled, and slowly as they have returned, life in Macedonia has become more Westernized. They used to sit on the floor, eat with fingers from platters of food as a family, and everything was cooked.” But that is no longer true, and as we are seeing all over the globe, cultural legacies are being lost.

Education Leading up to Noma

When he entered chef college, he became instantly smitten by cuisine. Originally, Redzepi assumed he was going to do his version of French food, but then he went to stage at El Bulli in ’98 – and ’98-2002 was a great time for the restaurant. “For me, I left that place with such a sense of freedom.” From there, he headed West to California for a stage at French Laundry.

At French Laundry, he was further energized. Here was a great Chef [Thomas Keller] with such a strong signature – “An American chef doing something American”, with ingenious dishes like “Coffee and Donuts”.

After traveling the world, the passion to do something new, unique, really something uniquely Danish, was solidified.

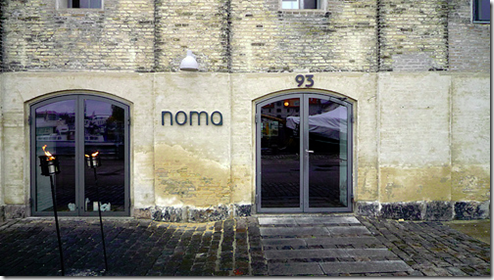

And so, seven years ago, he opened his first restaurant, Noma. He was 25.

Noma is located in the Christianshavn area of Copenhagen, Denmark. The building’s original use was as a warehouse for North Atlantic imports, and the rooms that the restaurant is housed in were used to store salt. The owners wanted a chef whose cuisine could in some way reflect the history of the place. And so, Noma moved in, with a noble goal of creating “high gastronomical cuisine using what was around us.”

At the time, basically all top level restaurants in Denmark were using European products. It was the standard. There was such a disbelief in the project. “It’s amazing how little faith we ourselves, the people, had in our own products.”

What unfolded was what Redzepi described by quoting Schopenhauer: “All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.” (Yes, the only chef I’ve heard quoting German philosophers.)

To put things in perspective about how hard they worked, Redzepi wasn’t happy even receiving their first Michelin star within a year of opening the restaurant. “At first, there were still too many reference points from other cuisines.” The idea of being local is easy. The difficult part is how you take “local” on the plate and make it work.

And so they started seven years ago rediscovering ingredients “so that they taste of their own place”. Chefs often read a lot of recipe books to draw inspiration, but Redzepi found that he needed to start reading other books – history books – to learn what people ate over the ages. And he spent a lot of time talking to historians.

As we listened to Redzepi describe this, Patterson shook his head in admiration: “There is a determination – Rene works a lot. He’s worked his ass off for years. There is a constant pushing.” To which Redzepi replied: “If you don’t have patience and commitment to the extreme and are not manic in your pursuit for this, it can’t happen. You have to work for this.”

Five Dishes

At this point, although I could have listened to hours of just conversation, we got to see a video of five dishes with notes from nature to plate. Most of the dishes at Noma are created with nature as the direct influence. Redzepi explains: “A lot of people ask “why is it so landscape-y?” It’s a reflection of where we go, walk, live….this is just the way things have shaped.”

The cuisine at Noma is so dependent on the weather and the seasons, it can change every day.

Redzepi began by introducing the ingredients he works with: “In Denmark, if there is any prejudice against our region, it’s that it is extremely cold and people think no ingredients can grow. But it’s a matter of determination and hard work.”

Taste is integrally linked to place. He explained (without prejudice) that things in America taste almost overly sweet to his palate – which happens to be because produce here has so much more time in the sun, than in Denmark where the flavors are much more mineralized because the plant gets nutrients mostly from the ground in their harsher climate.

Each dish has its own story, and unfolds with whim and novelty.

There was ‘Asparagus and Spruce’, where the green asparagus tips are grilled, then juiced. They add a touch of spruce oil, and then wrap white asparagus around actual spruce leaves, top with the juiced asparagus, and add a touch of whipped cream.

Or the ‘Steamed Oyster’, composed of the oyster, as well as plants sourced from the land around the oyster flats. So you have these native oysters, and then unripe pickled elderberry, and the dish is created by pouring seawater on, and steaming it in almost its natural environment.

Or “The Sea”, where a dish is composed from sea herbs rich in vitamins, sea water, rocks and beach plants. Topped with dried shaved urchin roe, arranged as if they were in their natural environment.

Or the ‘Hen and the Egg’, where the chef thinks what is a chicken? The whole dish is created from a starting point (the hen house) and the meal is created completely from ingredients a few feet around it. The egg, the hay from the coop, the herbs the hen eats. And then the whole dish is interactive – the diner actually puts together the dish and eats it.

My favorite dish however, was the ‘Vintage Carrot’, because it truly reflected the essence of the creativity on display at Noma.

A vintage carrot is actually a vintage ingredient.

They were having a winter like Ragnarök (the Norse mythological version of Armageddon), and it was “so crazy cold”. The chefs were running out of things to cook at Noma, and were desperately working with their farmers to find something they could serve. One farmer had these old hideous carrots he had left in the ground for a winter, and then stored them in his larder. They were year and a half old carrots. So they thought to themselves, how would you cook a carrot like this?

Maybe like you would cook a piece of perfectly aged beef – with as much care as possible. “So we wanted to do that with a carrot. What would happen if we gave the same care to a shitty old carrot?”

And so here is this dish, composed of vintage carrots, gently cooked with wild chamomile and sorrel in goats’ butter. They cook it, very slowly, an hour, hour and a half, and then suddenly it’s the carrot of their dreams.

And then he thought: SHIT. What if we are now eating the wrong carrots? What if this was the RIGHT carrot? The way carrots are supposed to be? The authentic carrot?

“So we asked the farmer – what other old shit do you have? Give us your crap! And then he got us vintage potatoes…” so the story goes.

CONVERSATION AS THE FOUNDATION

“The importance of people and the importance of conversation is just about everything for us.”

After fully transfixing us with food, the conversation returned to the work they put into the restaurant. Possibly the only frustration I have with the Noma book is that the front section on the day to day happenings of the restaurant is only a handful of pages. (Maybe that’ll be the next book.) Listening to Redzepi, these details are clearly things that he has thought long and hard about.

Noma has 20 full time employees, and 5-8 stagiers (interns – for one to three months) at any time, and the empowerment of each and every team member is an integral part of Noma’s success. The work is highly technical, and many people are involved in each and every dish. All this for forty covers a night. “The kitchen is full of good people, free thinking people – people who take standpoints on what they are cooking,” he went on. “Our trade is one of the last trades that will never be replaced by machines… you need to think”.

In addition to the hard working kitchen staff, they also work hand in hand with the farmers. Noma has a large network of farmers and foragers. They worked hard to cultivate these relationships. Just by giving feedback and respect to the farmers (a group of people, on the whole rarely congratulated for their hard work), they found these people striving to do better. “There is a sous chef in the kitchen to make sure the farmers feel that they are a part of us… They get Christmas cards every year, and every year they are invited to eat at the restaurant. We are having so many conversations with them constantly. If these people were not on the team, we wouldn’t have a restaurant.”

To further the education of his kitchen, Redzepi detailed several ways to make a better chef:

1. Make them harvest, prep, cook & serve. (Instill the feeling of giving.)

Each of the staff at Noma are taught to forage and harvest, which changed how the kitchen thinks about food. Chefs are usually trained to work within the format of recipes, but Redzepi knows first hand that chefs start changing when they really know how things grow. There is something so important about the conversation in nature, “I know it sounds a bit wacky,” Redzepi chuckled, “[but you need to have] a conversation with the plants in the forest. There is something so valuable about learning the essence of taste from the source in its perfect element. You know, the way it should be. How much would you allow yourself to do with this ingredient? [This] reflects how you treat an ingredient in the kitchen.”

How can a restaurant have the same feeling of giving if they charge for their meals? The chef was quick to make note that “in a perfect world, all restaurants would be free”, which he amended: “In a perfect world, all restaurants would be subsidized by the government.” [The audience laughed.]

By requiring everyone to have the opportunity to serve, you create better chefs. Actually seeing guests, they take a better standpoint on cooking. It’s the feeling you get as a parent feeding a child – you want to provide the best and most healthy and perfect food – they adopt the same philosophy for their diners.

2. Every Saturday they have an innovation practice in the kitchen, after service (about 2 am). Everyone has worked 75-80 hours or more. Each section has a head chef who creates a dish – the purpose is to “make chefs take a standpoint on what they enjoy about food.” In the beginning, it is very difficult – but week by week – people get better, stronger. They start really developing themselves as chefs.

This is one of the many reasons chefs around the world fight to work in Redzepi’s kitchen.

* * *

As the conversation neared its close, a member of the audience asked Redzepi “What’s next?” to which he replied:

“The biggest joy is now having complete freedom to cook what we want.” Redzepi laughed, “If we want to put reindeer balls… or beaver snout… we could put it on the menu, and people will try it.” Next is the same… until there is no more inspiration. “I have a personal vision of keeping learning throughout my life, and keeping my family learning.”

“Year by year, season by season, you start to understand more, and it starts adding up.”

* * *

As people filed out of the theater, my admiration was only reaffirmed, as René stood next to me while I sold books, and he personalized them, chatted, posed for photos, and put a smile on peoples’ faces.

Am I star struck? Maybe. A little. But, I’d like to think my jitters came from experiencing a critical moment – one where I was forced to think hard about what I had thought was true. I had to accept something new and profound. After seeing someone with so much passion, dedication, and thoughtfulness, a small part of me regrets not becoming a chef. But for now, I’m taking the time to think about what this will all mean for me. Who knows where life will take me?

And so, here, I share one slightly embarrassing photo that Emily took of us, (give me a break, I’d been working like a fiend the entire day), and would like to take a moment to say thank you to everyone who made this day possible.

Noma: Time and Place in Nordic Cuisine (Phaidon Press, $49.95) by René Redzepi, www.phaidon.com

What an amazing day you had — he sounds like an amazing presence. Great post! Theresa

.-= Island Vittles´s last blog ..Cuban Oregano Bhajis =-.

Sam, this is a fantastic post. Thank you so much for giving such detailed reportage. Now I can’t believe I missed out on such an amazing experience. But thanks for recounting it so thoroughly. I can see why you were moved by the entire event. Wow!

I am so envious. I get to review his book for Thermomix fans in the coming days but after reading your review of his lecture I am soooo sorry I wasn’t able to attend. Thanks for this lovely perspective and for taking 12 pages of notes!

.-= ThermomixBlogger Helene´s last blog ..What is the Easiest Yummiest Thermomix Breakfast CADA! =-.

Outstanding write-up, I really got a feel for the evening and Chef’s personality. And the photo at the end is fantastic, definitely one for the scrap book!

.-= Gudrun ´s last blog ..Promotions and giveaways &8211 how to reach your food blog audience =-.

This is a wonderful post, and I’m glad it went so well. I am so intrigued by the adventurous food combinations, and I’m sorry, but I have to disagree with you on something — you look GREAT in the photo. 🙂

.-= Serene´s last blog ..Udon and merging lives =-.

Great Post – it made me a little sad we didn’t have a similar experience at the Noma book presentation in Seattle.

Thanks so much Sam, I’m so glad you filled me in on what I missed! And I hope to be dining at your Michelin starred restaurant sometime soon 😉

.-= heather´s last blog ..Paella Party in my Garden! =-.

Thank you for taking the 12 pages of notes and writing this post! I didn’t have a chance to go to the event and having you write it up was the next best thing to attending it!

I have so much respect René and his sense of where food comes from and what it means. What a wonderful chance to host him at Omnivore!

And I have to agree with Serene. You look great in the photo!

.-= jackhonky´s last blog ..Dont Forget the Homos! BlogHer Food 2010 & gluten free chocolate cupcakes w- whipped cream cream cheese frosting =-.

Sam,

This is beautifully written and insightful. Truly enjoyable post. Thanks for sharing.

Gathering Nuts and Berries

Recently I attended a public conversation between famed Noma chef Rene Redzepi and local chef Daniel Patterson. The well attended event was held in conjunction with a book tour for the magnificent Phaidon publication about NOMA, Redzepi’s restaurant in Denmark, named top restaurant in the world. The audience was filled with young chefs waiting for revelations and revolutionary ideas.

Redzepi is a charmer, articulate, upbeat and unpretentious. I was interested in his decisions and thought processes. Yes, it must be very difficult to cultivate ingredients in such a challenging climate and environment, especially if you want to serve great food all year long. So you have to be resourceful and become a forager. This expands the repertoire of what you have to cook with and creates new and unusual harmonies on the plate.

Those expecting radical ideas may have been surprised with how un-radical many of his practices were. First he followed the old Mediterranean tenet that says “what grows together, goes together.” So oysters are paired on the plate with greens that grow near the shore and sea water used in the cooking. If spruce trees hover above the ground where asparagus grow, they are cooked together. Not a new concept but with such a limited larder, now see4mingly revelatory. His terroir is not our terroir.

Next Redzepi talked about how important it was to set up relationships with local farmers. Again, hardly a new concept here. In California we have been doing that for over thirty years. But we have it relatively easy. Unlike Denmark, California has a Mediterranean climate. We have a long growing seasons and a vast selection of ingredients at our culinary disposal. In fact some might say it has become a bit too easy and that there is danger of similarity of menu concept and all of the food tasting the same. Our chefs can source pretty much everything they need to create delicious food. To distinguish themselves from the pack some have started their own gardens so they can customize their produce. Even that may not be enough to get noticed. Other to seek differentiate themselves by making a show of adding foraged nuts, berries, native plants and roots on their menu, acting as if they too were stuck in the wilds of Denmark with not much to cook. Some might consider this sort of an affectation to get attentions.

Redzepi talked about involving his chefs in farming and foraging. We have restaurants doing that now. He talked of the practice of having the cooks come up with ideas for new dishes. This seemingly revolutionary concept is not new, except maybe to the men who have trained in the traditional European style hierarchical kitchen. Women chefs started doing this over thirty years ago. Now this idea of letting the cooks have a say in the food has trickled down to such formerly hierarchical chefs as Thomas Keller and Michael Chiarello. They learned it was lonely at the top and that collaboration promoted creativity.

After poking fun at excessive mechanical techniques like gelling, he got around to talking about the importance of a personal cuisine. Making traditional dishes as crème brulee with local wild berries did not make a new cuisine. It was still derivative of a Mediterranean culture. But what about those chefs in California living in a Mediterranean terroir ? Are they to throw it all away to be new? What about all of the melting pot cultural influences of Asia and Latin America? Are these to be disregarded as derivative, too? Do chefs have to imagine or pretend that they are living in the tundra or desert to create an original cuisine? This was the most provocative part of the evening and one that we will have time to ponder as we cook our way into the Twenty first century.

Hi Sam,

Thanks for this wonderful detailled post! I read it in one breath and in a way you were able to mix food,

star crazyness, philosophy, love, determenation into one bowl. It that sense it makes you a chef too 😉

I am so proud of you! Well done!

The hen and the egg sounds so neat. What a cool event to host.

Now, go get some sleep. 🙂

.-= Lizzy´s last blog ..Constructive Panic =-.

Wow. What a well written blog post -The MOABP! I regretted that I didn’t make but with this write-up I almost feel like I was there. Thanks Samantha!

.-= Robert B.´s last blog ..Grilled Pomegranate Coriander Shrimp with Broccoli MicroGreens Fennel and Citrus Salad and Dessert Focaccia =-.

Possibly the best blog post I have ever read. Brilliant! Lot of cool things happening over in SF, your write up was more insightful than any of the recent press articles I have read.

.-= Nick´s last blog ..Pane e Vino- Merida- Mexico =-.

I totally understand how you felt. Just a few months after seeing his Charlie Rose interview, I somehow found myself in Copenhagen. I thought, “I would love to meet two very compelling Danes: Rene Redzepi and singer Marie Fisker. But, what are the chances?” By some stroke of luck, I was able to get in for what ended up being a 4 hour lunch at Noma and met Rene. He took me on a tour of his incredibly clean and small kitchen, and spent some time talking about his favorite places in SF to eat. He is everything you say he is. And I was under his spell and yes, star struck! And I don’t usually get star struck. It was an unforgettable experience. Still feeling giddy after a few months!

As for meeting Marie Fisker, the gods must have heard me because later that day, I found myself sitting 2 seats away from her at a Hope Sandoval concert at the Vega. My seat mate introduced me to her and voila! My quest to meet the two most intriguing Danes (to me!) was complete.